Camp like a Pro:

Some thoughts on avoiding 'rookie mistakes' & getting the most benefit from training camps in your season plan

Alan Couzens, M.Sc. (Sports Science)

Over the course of my life as an endurance athlete and coach, I have been fortunate to attend a lot of training camps. Ranging from altitude camps with the Aussie National Swim Team to early season mileage camps with Pro cycling teams to a number of age group tri camps with EC & even an Epic Camp where we swam, biked & ran our way around New Zealand!

Recently, I was fortunate to add another to the list, when I got together with a few Pro's that I work with to lay some serious early season base in the Arizona desert. I figured, while the experience is fresh in my mind, I would pen some reflections on the above, particularly with regard to the things that I've observed from these experiences that define the best & worst ways to approach training camps.

First of all, an important question: What's the point of training camps?

I've said before that, for the serious competitive athlete, training camps are bordering on a necessity.

For the competitive age-grouper, time in the context of a regular work week becomes a real limiter and by removing some of the normal time constraints periodically, the serious AGer can get a significant 'step up' on their time constrained rivals.

On the other hand, for Pro's, due to the frequency of racing, the space for adding fitness within each build is constrained & it really takes regular use of these high training density periods to make any significant inroads from one build to the next.

In addition to time, most folks underestimate the power that comes with the simplicity of 'camp life'. Looking at the numbers of life stress ratings and training load, I've observed that an athlete's ability to tolerate load is consistently inversely proportional to their life stress. By periodically removing yourself from the stressors of 'normal life' and surrounding yourself with some fellow crazies whose common, sole (soul) focus is to train, eat, sleep, repeat, the difference in your ability to absorb load is likely to be surprisingly substantial.

This context brings us the the first and foremost consideration when planning your training camp(s): It is absolutely essential to go in with a clear expectation of what you hope to get out of it. Getaway camps represent a significant financial investment and it is important to get a worthwhile return. This 'return' can take a number of forms. Not the least of which is the 'happiness return' of spending your vacation time doing in a nice place, doing what you love! But, typically we also want another return on our investment in the form of a fitness boost that you can make full use of in your A Race!

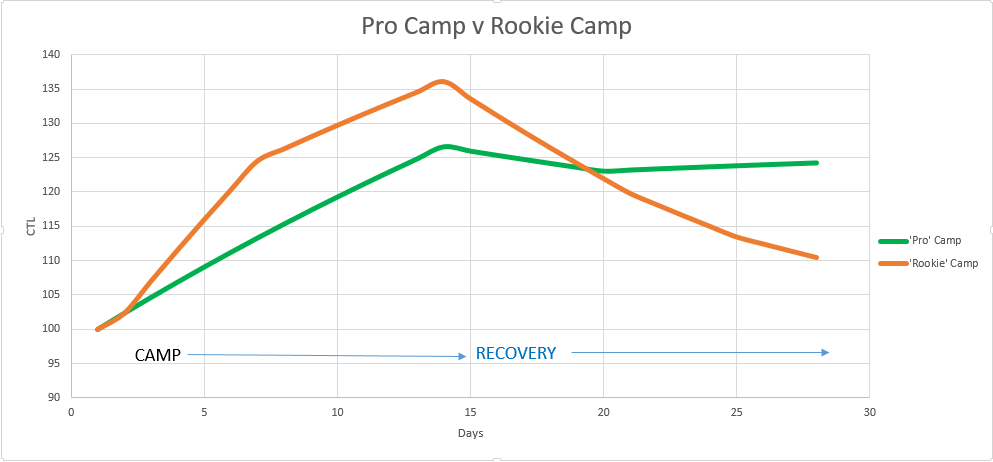

A little more 'geekily', especially for an early season camp, we want the athlete to get a significant CTL 'fitness boost' from the camp (something in the range of 20-30 over the course of the camp). This sort of big CTL ramp is very tough to achieve in 'normal life', especially for athletes who already have a relatively high level of fitness. But, even more important than the initial boost, we want the athlete to be able to 'hold onto' the fitness they build after the camp! We don't want the athlete's season peak to be at a training camp!

Unfortunately, the above chart illustration of making a few 'rookie mistakes' in training camps that lead to extended recovery & a loss of the hard-earned fitness gained at camp is all too common. Without a plan, athletes have a tendency to go crazy during the beginning of the camp & achieve a fitness peak early in the camp that they struggle to recover from quickly enough to hold onto & so, as the chart shows, the fitness gains made at camp get slowly whittled away during extended recovery.

The 'success' of a training camp should always be assessed not purely over the duration of the 'loading portion' of the camp but also the 'recovery portion'. A successful camp has the athlete adding a lot of fitness *and* recovering quickly enough to hold onto that fitness. Nothing is sadder than to see an athlete expend a lot of time, money & energy(!) in a training camp only to run at a 'net loss' of fitness due to extended recovery following the camp. This scenario is easy enough to avoid by simply arriving at your camp with a plan & by making a concerted effort to avoid a few 'rookie mistakes'...

Pro tip 1: Be sure to go into the camp with some good basic fitness

The big advantage of training camps is that you can remove a bunch of normal life 'time sucks' & 'energy sucks' & truly focus the day around training and recovery. It is nothing short of amazing to see the effect that this has on an athlete's ability to lay down some serious training volume. For a short period of time, athletes can often handle up to double their normal weekly training volume simply by removing all of those other sources of stress that typify daily life & by having the space to put more emphasis on sleep, eating and just hanging out on the foam roll watching funny movies.

The above withstanding, in order to make the most use of your ability to train all day, the athlete needs to come in with some level of foundational fitness. In my experience, in order to properly absorb & benefit from the camp load, the athlete should come in with a CTL of no less than half the target TSS/d, i.e. if the average camp load is 200TSS/d, I would want an athlete to have a 'foundational fitness' of at least 100 CTL coming in. This was a high priority in getting these athletes ready for such a big load. In this case, Inaki & Leo were coming off a lighter 'lead-in' coach-athlete camp in Merida & Mags was coming off some serious(ly fun!) strength-endurance winter conditioning in Tremblant.

The need to fit in these preparatory blocks has implications on the best timing for camps. For a 'base camp', with a focus on the development of aerobic fitness, we want it to be far enough away from the key race to still have time to transmute that basic aerobic fitness into race specific qualities, but we also want it to be late enough in the build that some level of foundational fitness has also been developed.

Pro tip 2: Go in with *your* plan.

It is scarily common for an athlete to rock up to training camp without their own plan forgetting that, unless the camp is being explicitly programmed by your own coach that the folks who put the camp together know very little about you and where your training is! Similarly, it is common for an athlete to get together with a couple of buddies with an attitude of 'we'll just train until the legs drop off' for a couple of weeks, forgetting their long term training progression. Either way, it's a BIG mistake to not have some sort of load target in mind when coming into a training camp. 'Until detonation' is not a strategy!

Pro tip 3: It's a training camp, not a stage race!

Always keep in mind, it is a training camp, not a race! The company is there as friends to help the miles go down a little more easily, not as rivals to beat up and assert your dominance over! If there is one clear distinction between experiencing a well run pro vs an amateur camp, it is here, in the culture of the camp. Pro athletes work together to get the job done. Amateur athletes have a tendency to 'test' & work against each other. This was my first reminder after watching the crew working together like a well oiled machine on the first big day of 200+K - eating up the miles at an impressive steady, constant rate, getting their target work done in their respective zones by working together as a team...

Over-doing the intensity might be the most common 'rookie' mistake and it is bred from a very primal human fear of 'not keeping up'. In addition to having load/volume guidelines going in, it is just as important to have intensity guidelines. This is not to say that the entirety of the camp is easy or that the athlete can't have a little fun 'mixing it up' but it is important to identify before-hand just how much intense work you are planning for the week.

It is very easy, especially when coming into the week with a little freshness, to fall into the habit of doing a lot of work that's 'one gear up' on your normal base intensity by 'hanging with the fast group' on each and every day. With a bit of freshness, this is doable for a few days but it leads to a mid-camp hole that significantly compromises the overall value of the camp. A smarter approach is to identify the spot/group that puts you in that Z1-2 for the vast majority of the time, especially early in the camp &, in the wise words of another buddy, Justin Daerr - let the work come to you. You will tend to find that if you can just hold output & a fairly constant load over the camp, you will progressively transition your way up/through the groups as others tire. Very much like an Ironman race.

The more common scenario (like in the 'rookie chart' example above) is that the athlete puts out 300TSS/d by cranking the intensity up for a few days early in the camp and is then spent and struggling to get 150 due to inability to hold any sort of worthwhile intensity late in the camp or upon return home.

In the case of this camp, almost 90% of the accumulated load was in the easy-steady (Z1/2) zones with only a few 'special efforts' - a cruise interval session for the run, a threshold bike up Kitt Peak and a couple of 'hill reps' up a 26mi/+6000ft 'hill' called Mt. Lemmon :-)...

Knowing these were coming later in the camp, the athletes kept the rest of the volume pretty chill.

A good part of 'keeping it chill' is finding the right camp, the right group and the right wheel.This will enable you to save the Zone 3+ for those 'special efforts'. The opportunity for these special efforts will often show up at surprising times. It is nice to have the legs to respond to those opportunities :-)

Pro tip 4: It's a training camp not a 'spring break' party :-)

With the mix of excitement and cortisol that comes with spending time with like minded crazies, it can be tempting to 'keep the party rolling' off the bike, and in so doing, compromise recovery from the big sessions. When done right, the social aspect of camps can offer a real boost to the athlete's recovery. Per the above, things that switch the recovery systems on like hanging out together on foam rolls chatting & watching a funny movie before bed = good. Going out for drinks after training and hanging out late in the bar doing shots of Crown = bad :-) In the words of my buddy Gordo Byrn, choose wisely.

Pro tip 5: You're putting out a crazy amount of calories (& sweat). Make sure you replace them!

I got a bit of heat after posting this instagram reminder that, when it comes to camp, the emphasis is on quantity nutrition more than quality nutrition. I stand by it completely *on camp*. If you are not downing a good amount of simple sugars on camp, your ability to tolerate the load will be compromised (& the incidence of those Z0 low energy days will be greatly increased). Training Camp is definitely not the time to give that new magic Keto diet you've been hearing about a whirl :-)

On a big camp, an average sized athlete will be expending 5-6,000 kcal/day and 2500-3000kcal (~600-700g) will come from Carbohydrate. The athlete simply has to keep up with this output in order to sustain their energy over the camp and it is near impossible to do that 'eating clean'.

Athletes training at these volumes can 'get away with this' (and, indeed, require this) because at this level of energy demand, there is almost no risk of excess sugar hanging out in the blood or being converted to lipids. With the constant energy demands (& perpetually low energy stores) any and all sugar ingested is quickly taken up by the muscles and stored as glycogen ready for the next metabolic assault! If you want to prove this, take a glucometer along with you. High blood glucose is very hard to come by during periods of high energy expenditure like a training camp. Hmmm, there might be something in that observation for all of us.

This is not to say that when camp is done, the diet needs to progressively head back to an emphasis on quality over quantity. But for the duration of camp the most important thing that an athlete can do for their recovery and their overall health is to ensure that they keep up with energy demands and avoid pushing the body into a catabolic state. High training volume coupled with energy deprivation is a sure-fire route to chronic fatigue & long term overtraining.

Pro tip 6: Expect a few rough days

A reminder: This is not regular training :-) While, in the context of a normal training week, the inability to hit a session might be a bit of a red flag, over the course of a training camp, it is to be expected. Even with proper fueling, with the big load, camp energy goes in waves for all. Some days you're the engine, some days you're the caboose. This is a very normal phenomenon in training camp world. Everyone has good and bad days in accordance with those waves of glycogen depletion and repletion. It becomes problematic when the athlete isn't OK with this and wants to be 'on fire' each day. Pushing for Z3 watts on a day when the legs only have Z1 in them is a recipe for digging a hole that is very tough to climb out of.

Pro tip 7: Don't stay too long

Even when everything is done right (intensity, fueling, listening to your body), eventually those energy stores will start running out of gas. When the intensity is correct, this shows up as a gradual wind down (when the intensity isn't correct it shows up as a perpetual 'tired but wired' sensation. It follows that my first qu to the athletes on waking each morning was "how did you sleep?"). Towards the end of camp, usually somewhere between 7-14 days, when the body is starting to run out of gas, athletes start to get a bit generally bonky, a bit sleepy, a bit loopy...

Gordo used to call this 'fatigue intoxication' & it showed up again in the best possible ways towards the end of this camp :-) It goes without saying (but I'll say it any way) that, when this pattern starts to show up on successive days, that you should listen to your body, call it a camp and go home & rest! Bad things happen when athletes try to 'keep it rolling' on zero energy stores. Apart from the risk of injury that comes with training while 'loopy', when glycogen stores are empty, the body goes into survival mode and will start tearing you down in order to get the job done. Good, effective camps are all about building you up, not tearing you down.

Pro tip 8: Train hard on camp. Recover equally hard when you get home!

In a similar vein to the nutrition, it can be a big paradigm shift to swing between the extremes of big training and regular life. During training camp, the body can get into a rhythm of getting up, doing big training, eating, sleeping & it can be tempting to want to keep that rhythm going when you get home. Athletes are often suprised by just how well they are able to tolerate training in the context of a camp environment and that inevitable follow up question emerges - "what if I could keep this going over multiple, consecutive weeks in the year?" Let me save you the suspense, you can't :-) Going back to the first rookie mistake, camps represent a significant load ramp over the training coming in. They are fine (& beneficial) in small doses but, when we try and sustain this ramp, injury, illness &/or overtraining are inevitable, leading to a need for *extended* recovery where the athlete will lose the fitness benefit of the camp. Remember, we want the camp to be a season 'stepping stone', not a season peak.

Pro tip 9: But don't shut it down completely when you get home.

On the flipside, it is equally detrimental to go 'cold turkey' when you get home. Camps represent a very real 'shock to the system' and it is equally important to 'taper out' of camps as it is to 'taper in'. Where time allows, a good strategy is to leave a couple of days buffer on either side of camp to ease back into 'normal life'. Ideally, this might be doing your own thing at the camp venue but if it is at home, give yourself a few days of active movement & lighter life stress before you really get cranking on that inbox :-)

#####

In summary, training camps, when appropriately timed and executed can give you the sort of fitness bump that is very tough, if not impossible, to achieve in the context of 'normal life'. As such they are an integral part of the serious athlete's annual preparation. Undoubtedly, camps offer the potential for a very high reward, but they are also a time of higher risk, where it pays to be cautious and very strategic in order to guarantee that you get a very worthwhile return on your investment that you can apply to the larger goal. At all times of the year, but especially during training camps, it pays to...

Train smart,

AC

TweetDon't miss a post! Sign up for my mailing list to get notified of all new content....