Training Response Curves: Are you a long responder?

Alan Couzens, MS (Sports Science)

April 17th, 2015

In a previous post, I talked about the different types of athletes that I work with – the fast responding ‘Naturals’, the average responding ‘Realists’ and the slow responding ‘Workers’. This is a simple way to view the way that a given athlete responds to a given training load but the reality is a bit more complicated than that, as it neglects those 2 words that are the bane of athletes the world over – diminishing returns.

In performance modelling, diminishing returns is accounted for, to some extent in the exponential nature of the dose-response model, i.e. if an athlete loads at 100 TSS/day, their CTL curve will improve rapidly at the start, will taper off around month 3 and will flatten out by month 5 (assuming the default 42 constant). But, the model doesn’t go far enough....

In the case of a long season, an athlete’s performance can actually regress despite an increasing CTL!

That’s right – more training load but less fitness!

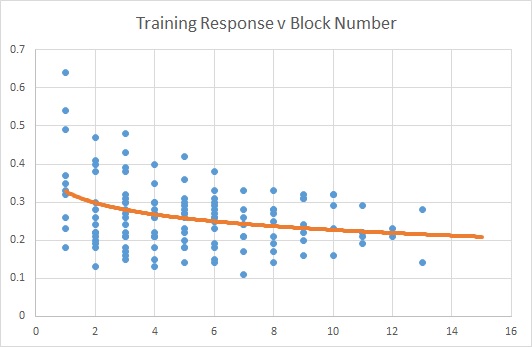

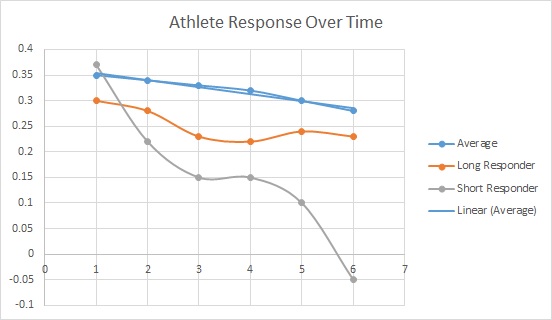

In this post, I offered a way to quantify the athlete’s response to the training load. If you do this over time (from month to month) you will see that this ‘response coefficient’ progressively drops over the course of the season. I returned to my database with pick in hand (using the same method as referenced in this recent post) to see if I could 'mine' the answer of just what the average curve of diminishing returns is, over the course of a season. Here is what I found....

The 'average responder' starts the season with a response coefficient of ~0.35. This progressively falls over the course of each month and by the time they are 12 months in, they are getting just a little more than half of the (fitness) "bang" for their (training) "buck" that they were getting at the start of the season. Put another way, if it 'costs' an average athlete 10CTL to get a given rise in fitness in the first block, that same rise in fitness will cost them 20CTL by month 12.

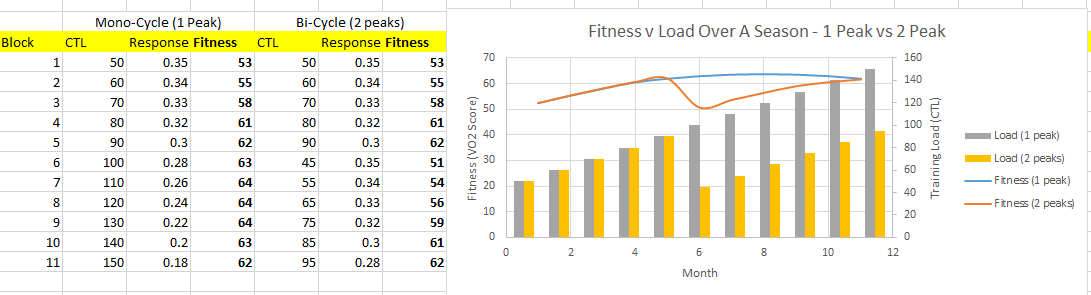

This is a key consideration when planning the length of your season. With a full unload, an athlete will typically lose ~50% of their CTL. So, for an average athlete, 2x5month builds, with a mid year unload vs a full 11 month build can offer very similar fitness benefit with less overall training load to a full year build as played out below...

The benefit of the second approach of throwing a 're-energize' block in there are summed up very eloquently by 'Honest Abe'...

Mr. Lincoln would have made a fine coach! Same principle applies here. Maybe the athlete can't quite afford 4 'sharpening the axe' blocks in a year but there may certainly be some benefit to including 2. Put more bluntly, 'type A' athletes shouldn't automatically assume that more work equals higher fitness. They should periodically 'check in' to make sure this relationship is still holding! They also shouldn't under-estimate the positive benefit that rest can have on a tired system!

So, 2 builds per year is the magic recipe? Not so fast!

While that trend line of diminished response shown above represents the mean, you'll see there is a large range of responses across each block. Which brings us to the title of the post. Are YOU a long responder?

If we compare across athletes in the scatterplot above, you’ll see that the rate at which training response drops over the course of a season varies a lot! This has important implications when planning the length of the training build for a given athlete. It doesn't matter so much how the average athlete's response to training changes over time. The important question is, what's your pattern?

I’ve shown 2 examples of ‘real life’ athletes below to illustrate the point….

While both athletes get less performance ‘bang’ for their training ‘buck’ over the course of the season (as they accumulate fatigue), one of the athletes reached a point of zero return by 6 months in. At this point, the system was simply too tired to adapt to an increase in load, and if we decided to continue to load, bad things can happen. Trust me on that!

On the other end of the spectrum, athlete B, the ‘long responder’ has more of a linear drop and will continue to gain fitness over the course of a longer prep.

These differences come into play significantly when I’m working with an athlete on season planning &, along with time limitations, can directly influence the choice of whether a bi-cycle (2 peak) or monocycle (1 peak) annual strategy is most appropriate.

If you are in the process of planning your season, I highly recommend going back over your last year (using this calculator) and looking at how your response changed over the course of your last season. This is a high value exercise in determining how to structure your season and when to plan your peak events

The above withstanding, while there is some level of stability in these patterns, other factors can come into play that may increase the rate of fatigue on an athlete’s reserves and lead to diminished adaptation earlier in the season than might have been expected (a lingering sickness, a stressful period at work etc). For this reason, it is important to maintain a level of fluidity and flexibility in race scheduling and the overall structure of the plan and when signs of a long term plateau begin to show up, it’s time to take a break from chopping and sharpen your axe.

Train smart,

AC

Tweet**************************

Don't miss a post! Sign up for my mailing list to get notified of all new content.