A physiologist's take on 'MAF' training

Alan Couzens, M.Sc. (Sports Science)

April 3rd, 2015

As far as I’m concerned, the guy to the left is *the man* when it comes to healthy, sustainable training for endurance athletes. Dr Maffetone is one of the few that gets that...

Fitness = Training x Your body's response to training (i.e. your health!)

....and pays EQUAL attention & focus to both sides of the equation.

“MAF” training (maximal aerobic function) training was a term coined by Dr. Maffetone back in the 80’s. At the time he was coaching a young athlete by the name of Mark Allen. You may have heard of him? :-)

Despite the obvious success of the approach in Mark Allen’s career (& a host of other notables, like Mike Pigg and the Deboom brothers), if you find yourself bored enough on a Friday afternoon to sift your way through one of the 'office-chair expert' internet tri-forums, you’ll no doubt find a thread proclaiming the method as ‘unscientific’ or ‘quackery’. These same posters will then go on to quote the ‘proven’ (in a 6 week study on untrained subjects :-) efficacy of an approach like high intensity interval training.

Much of the criticism is centered around the ‘MAF formula’ - used to approximate the upper limits of the target heart rate training zone. The 180-age formula has received a lot of criticism for its lack of consideration of individual differences in heart rate. I’ve got some news for you…

Just about ALL estimation methods are prone to these errors in assumption but few seem to receive the same level of criticism as MAF!

For instance, do you use a 20 or 30 minute test to infer (60 min) FTP by taking an arbitrary 5% from that number? Guess what, there are huge individual differences in the relationship between any given athlete’s 60min & 20min power numbers (& for the vast majority it’s not 5%!).

Any estimation method is prone to these errors but this doesn’t discount the benefit of estimation methods as a starting point for a large population. I (and, I’m sure, Dr. Maffetone) would love every athlete to get frequent, individual lab data but for many recreational athletes with budget concerns, that isn’t going to happen so we’re left with the next best (still good) 'real world' option – a readily applicable, easily repeatable, estimation method.

Most importantly, let’s not 'throw the baby out with the bath water' & miss the really important bit in the MAF approach – identifying a critical point that represents a real shift between healthy,low recovery cost, ‘fat-burning’ training and high risk, high recovery cost, ‘sugar-burning’ training.

So, where does this critical point lie on a traditional metabolic test?

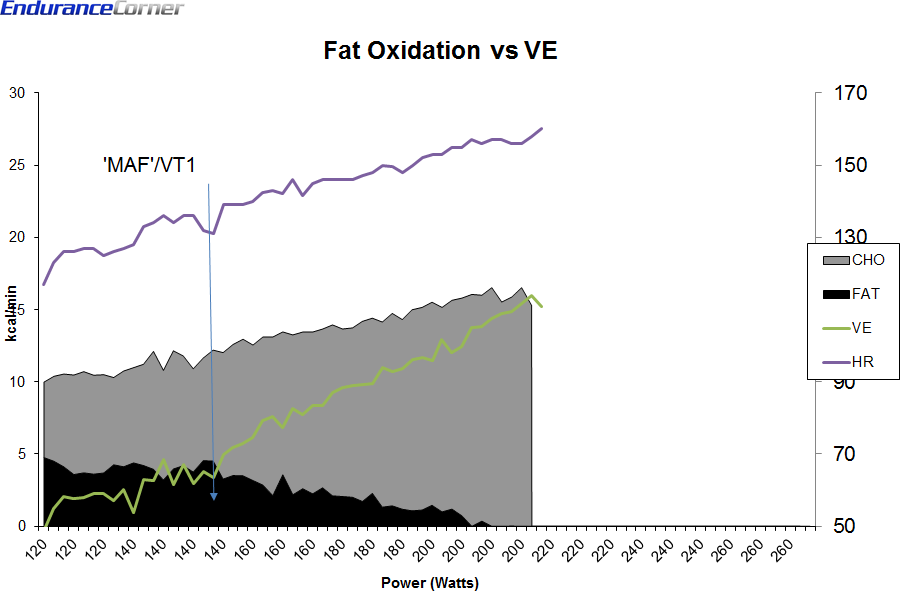

The following chart shows the data from a very typical metabolic test. Fat oxidation is in black, CHO oxidation is in grey. The green line shows the ventilation of the athlete, while the purple line shows heart rate.

You can see an obvious metabolic shift that occurs, for this athlete, at approximately 140 watts or, (for this 40 year old athlete) a heart rate of 140bpm. Ventilation begins to rise (breathing 'deepens') & (at the same point) fat oxidation begins to drop off markedly, moving from a nice, strong, max of 5kcal/min down to approximately half that by the next 20W stage and down to zero within another 2 stages. This metabolic shift has serious implications on recovery for any training done beyond this critical point!

While fat stores are abundant for even the leanest athlete, CHO stores must be replaced between each workout. The difference for this athlete between 140 and 160W is a difference of ~300kcal extra CHO expenditure per hour! For a 4hr workout, and average glycogen resynthesis rates, this could amount to an extra 12hrs of recovery! And that’s not the worst of it…

The greatest enemy to serious, working athletes are the terrible twins of illness and injury. Both of these have a tendency to ‘pop up’ when stress is high and the capacity of our nervous system to handle that stress (indicated by heart rate variability) is low, a concept I explore further here. The type of training that you choose to do can have a significant impact (for good or bad) on your overall systemic stress.

Stephen Seiler & colleagues (2007) looked at the question of the impact of training intensity on stress to the nervous system and found that there was one particular point that separated “high stress” and “low stress” training. That point was VT1 or the first significant rise in VE/VO2. On our chart, the first significant ramp of that green line - a point coiniciding (unsurprisingly) with peak fat oxidation and with the athletes ~MAF heart rate.

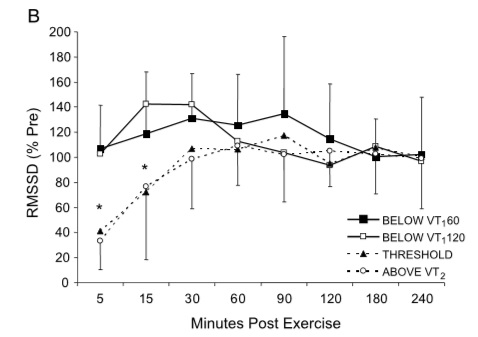

As the chart below illustrates, Seiler found that sessions below VT1 don’t hurt the nervous system at all, in fact they seem to give the parasympathetic system a bit of a boost (above their '100%' pre-training session level) that may help the athlete to better deal with other sources of high stress - whether they come from anaerobic training sessions or an irritating boss!

This also ties in with studies on hormonal response to exercise intensity which show a significant increase in gluco-corticoid (stress hormone) secretion with higher levels of intensity. Remember, cortisol is a catabolic ‘tear you down’ hormone. OK in small doses but not as a staple, especially for the athlete who gets a dose or 2 of it already from his/her office job!

In a performance sense, the emphasis on spending a good portion of the year with a focus on sessions within your 'MAF zone' is all about “training to train”, i.e. improving the ability of your system to absorb and respond to specific (hard) work. All of this ties in. As I’ve previously referenced (Hautala, 2004), athletes with a high parasympathetic response, respond well to hard training (when the time is right) – they get more performance bang for their training back than athletes with lower (HF) heart rate variability/less of an aerobic base. As the above shows, the best way to boost up your parasympathetic numbers is with training below VT1, below your MAF heart rate. If you're like most of the age-groupers I work with, your parasympathetic system could probably use a little extra attention!

Take home points….

- Don’t (buy the internet hype) and overlook the proven long term value of the Maffetone approach because (in this overly complex era) you’re too put off by the simplicity of the formula!

- If you want to fine tune your own personal MAF heart rate, by all means get a metabolic test.

- Whatever you do, don’t miss the gems! Training at or below this point will:

* Significantly improve fat oxidation - a critical performance factor for Ironman athletes,

* Significantly diminish the recovery time between all sessions (improving my precious – consistency)

* Help you, the working age-grouper, to steer clear of the terrible (season destroying) twins of illness and injury.

* Counteract some of the other nasty stress in your life to maximize your chances of staying healthy!

Train smart,

AC

Tweet