The lure of Anaerobic training

Alan Couzens, M.S. (Sports Science)

May 1st, 2015

As spring rolls around and uber-fresh athletes become reacquainted with their Strava accounts, the temptation for an emphasis on anaerobic efforts in training is ever present. Keeping athletes away from the “dark side” is made all the more tough for (good) coaches by the potential for quick improvement that anaerobic training offers.

The good….

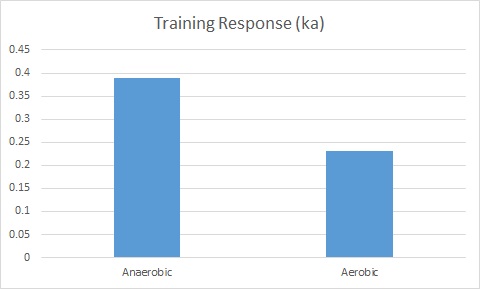

Athletes who undertake a period of anaerobic training will frequently see a quick boost in power:HR numbers over the course of the block, an improvement rate a good bit greater than what they would expect from the same load in base training.

Quantitatively, this can be in the range of 2 times the ‘performance bang’ than an athlete might get from the same load of base training(!) ‘Real life’ data from one of my athletes who recently completed a period of anaerobic ‘sharpening’ is shown below in the form of training response numbers.

This guy has a VO2max nudging up on 70 and is a perennial Kona Qualifier, which makes the significance of these response numbers all the more powerful – he was already a fit dude going in!

For these blocks of anaerobic training, we nudged up his training load from his norm of ~5% of work at or above the anaerobic threshold up to ~20% of load at or above the anaerobic threshold. This took the form of 2 hard sessions per sport per week & you can see the impact this intensity shift had on his training response.

Putting this data in more directly applicable terms, by significantly increasing the amount of anaerobic load, an athlete who typically adds 10W to his FTP over the course of a base training block might add 15, or even 20 watts, with a good block of anaerobic training! Good deal, right?

The bad…

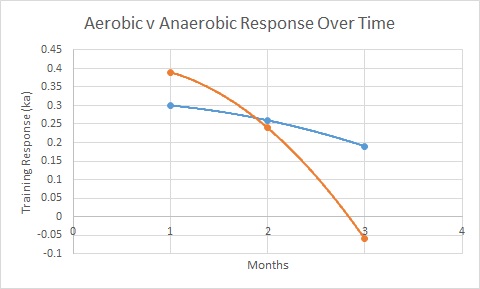

In a previous post I talked about ‘response curves’, i.e. how an athlete’s response to a given training load changes over time. I outlined a pattern of diminishing returns for aerobic training. So, what about anaerobic training? The prognosis is far worse!

For that first block of anaerobic training the athlete may, indeed, add 20W. However, if he does another, that rate of improvement is likely to be in the range of half that – 10W for our average athlete. If he manages to pull off another after that (without sickness or injury), based on my experience, he’ll be lucky to get any benefit from the anaerobic work. If we return to the athlete mentioned above, this is shown graphically below …

Here we compare 3 months of base training early in the season with the 3 months of anaerobic training. Good deal month 1, decent deal month 2, horrible deal month 3! By the 3rd month, the athlete actually had worse overall power:HR numbers despite a higher chronic training load.

Of course, this is n=1 data but, while the details may differ among athletes, based on my experience, the pattern of steep diminishing returns holds. Furthermore, when this athlete goes back to his basework he’s going to be left wondering “where did my base go?”

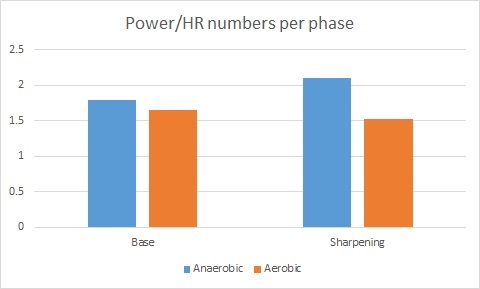

When looking at summary data from the first block of anaerobic training, the overall trend in power:HR numbers is good. However, if we drill a little deeper, you might start to notice a disturbing trend. While overall power:HR numbers look good, if we look at it on a per workout basis, the numbers from long aerobic workouts start to head South. For long distance athletes, this is important!

Here we break the power/HR (EF) numbers down for each phase. For anaerobic workouts, the sharpening workouts create a significant boost. However, the orange aerobic numbers actually get a little worse.

Physiologically, the reason for this is simple, your Type IIx fibers are a little ‘bi-curious’ - they can go either way… but not both ways. If you train them to be efficient in the production of energy from anaerobic glycolysis, the ‘inner machinery’ will be primed to make the most from this pathway and they will become less efficient in the development of energy from aerobic means.

The ugly…

While the diminished response you get from extending anaerobic work for too long is a bad thing, it’s not the worst of it….

The real problem with extended periods of anaerobic work occurs on the neuro-hormonal level:

If you do a lot of aerobic volume you get tired: Falling asleep in the middle of the day, no energy to train, happy, sleepy, tired. If you do a lot of anaerobic volume, this tiredness is masked for a period of time by an important survival mechanism designed to enable you to ‘carry on’ during ‘emergency situations’ of high stress.

This type of tired manifests as agitated, ‘everyone and everything is pissing me off’, ‘stay the hell away from me’, ‘I’m gonna get in a fight’ type of tired – much less pleasant, much less healthy and much less conducive to your overall sanity!

If we look at HRV values of athletes in the midst of anaerobic training, we see this as a drop in parasympathetic activity that precedes any drop in sympathetic activity. In other words, the athlete’s body prioritizes getting the work done even when their ability to relax and recover from said work is compromised. The more intense the work, the more of a gap we see here between the time that the ‘rest and repair’ system tanks and the time that the ‘do work’ system finally begins to wind down. This is a very dangerous period of time where the athlete can do serious damage to their adrenal system. At the extreme, damage that can take many years to recover from.

****

In summary…

- Anaerobic training is a powerful (but short lived) training stimulus.

- Athletes should insert frequent but short periods of anaerobic training in their training build (3-8 weeks)

- For the bulk of athletes, aerobic blocks should exceed anaerobic blocks in the ratio of at least 2:1, ideally 3:1.

Anaerobic training is an important and powerful element in an endurance athlete’s arsenal. Used properly, it can provide a short term turbo boost to an athlete’s training response. Used improperly, or for too long, it can destroy an athlete’s season, or worse, an athlete's long term health!

Train smart,

AC

Tweet**************************

Don't miss a post! Sign up for my mailing list to get notified of all new content.

**************************